Sunday, December 14, 2008

Tryst and Shoot

"That 'Camera' should have waited 20 years to find an English-language publisher is scandalous. That the wonderful Dalkey Archive has taken on the task is unsurprising. While Toussaint’s long, chatty sentences sometimes trick the translator Matthew B. Smith into losing his syntactical thread, this version admirably renders the frankness that makes Toussaint so alluring."

It is refreshing to read a review of a novella that doesn't mention "novella" or any of the other slim gem words.

Friday, November 21, 2008

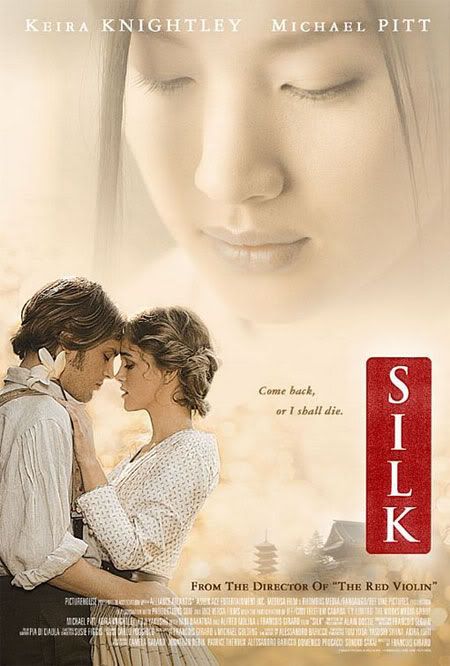

Silk

In what ways can unrequited love occur? The classic tale requires that one falls for another who cannot return the love, and its variations are manifold. Alessandro Baricco's Silk imagines unrequited love happening between the last two people on earth that we'd expect.

In what ways can unrequited love occur? The classic tale requires that one falls for another who cannot return the love, and its variations are manifold. Alessandro Baricco's Silk imagines unrequited love happening between the last two people on earth that we'd expect.Hervé Joncour travels from his village in France to Japan once a year to purchase the silkworm eggs necessary for his village's industry. While in Japan, he falls for his contact's concubine, the only woman in Japan without oriental eyes. He never speaks to her, but she does give him a short letter. He returns to Japan several times, partly on business but mainly to see this woman again. Eventually, war intervenes and his trips must end but he receives a final letter written in Japanese that will unravel his life.

Each chapter is meticulously brief. Baricco's prose is as light and effortless as finely wrought silk; it rests delicately upon the tale. Although Silk could be read in a sitting, reading it at a rapid rate is barbaric. I wanted to linger over each page and luxuriate in each scene and bask in the sparse, yet intimately revealing, dialogue. Like rubbing the finest silk between your fingers, feeling its airy nothingness and wispy delicateness, Baricco's novella slows you down into a state of quiet wonder as you marvel over how such a thing could be made.

It is a cliche that the highest praise offered for prose is that it reads like poetry. Perhaps this is true of this novella, though I'd prefer to go overboard and call it prose poetry. Words and meanings are compressed into the smallest of possible spaces, but still allowed to range across the page and across a tale in their sometimes quickstep and sometimes ambling rhythms. Prose poetry is difficult enough to define, and the same difficulty of definition haunts the novella. Throw the two together and a patchwork portmanteau genre is created, the prose poem novella.

Of the many ways of representing love on the screen, three are currently in style. The raucous, humorous path of ribaldry is common enough, as is the vulgar and impatient voyeurism of pornography. Though the erotic may contain elements of both ribaldry and pornography, it tends to favor the slow glance rather than the mocking stare of ribaldry; it favors the lingering touch, not the interminable pounding of porn. The erotic is subtle and nuanced. A body is nude, not naked; to not know the difference is to not know when the erotic is present.

François Girard's film adaptation of Silk is an erotic film that revels in understatement. Visually alluring, it is a patient film filled with exquisite moments: the tea ceremony where Hervé first notices the concubine; Herve sitting by the window and watching Hélenè wander the garden with a lighted globe; the bathhouse scene is a delicate depiction of seduction.

Michael Pitt (brother of another famous Pitt) does a decent job as Hervé Joncour. Though it is a subtle performance, it isn't very detailed. Kiera Knightley is even-handed, and her potrayal of Hélenè is weighted toward the beginning and the end without much in the middle. A better Baldabilou could not have been found than Alfred Molina. The moment he appeared I nearly jumped from my seat to shout, "It's him!"

Though just over one hundred minutes long, Silk caresses each minute. Some reviews I've read complain that the film is slow, a criticism that makes me wonder if the book had been read or if the reviewer was just another contemporary victim of caffeinated carnality, unable to slow down and meander through this garden of a film. For such a speed freak, I wouldn't recommend Silk. Perhaps coarser viewers would prefer Burlap?

Friday, November 7, 2008

Thursday, November 6, 2008

A Slack, Boneless, Affected Word

All four of them (Old Mortality; Noon Wine; Pale Horse, Pale Rider; The Leaning Tower) are collected with other works, including the oft-anthologized and masterful "The Jiliting of Granny Weatherall," in the lastest one-volume edition from Library of America.

More about her and this volume can be found here.

Tuesday, November 4, 2008

From A to X: A Story In Letters

"His most recent novel, 'From A to X: A Story in Letters,' plays with form in several ways: from the trompe l’oeil cover, which suggests the object in hand is not a work of fiction but an actual dossier, to the preface, in which someone named John Berger explains that he has come into possession of three packets of letters 'recuperated' from an abandoned prison. These missives were written by someone called A’ida ('if this is her real name') to her lover, 'known as Xavier,' jailed as a founding member of a 'terrorist network.' By telling us the letters are not in chronological order, by proposing that their contents may be written in code and by indicating places where the writing is illegible, Berger the author invites us to interact with, to co-create, the text, guessing at the meanings of words and phrases, pondering what might have happened in the interval between letters, and imagining the reasons some were never posted. But 'invites' is too mild a term, and 'co-create' too academic. What he really does is charge the reader with the responsibility to join in."

Though the reviewer calls it a novel, Berger's book weighs in at 197 pages.

Monday, November 3, 2008

Toni Morrison: a place out of no place

"A Nobel Prize winner, Toni Morrison is an American literary institution by now, and one can expect this short novel to draw plenty of admiration. For its originality, its bravery in tackling a time that's difficult to access, its egalitarian depiction of America's foundation on the unpaid labour of many different races, and its beautiful turns of phrase, it will have earned that admiration.

[...]

Sunday, November 2, 2008

A Debut of Distinction

"But the subjects coalesce in the highly readable and involving novella, 'The Republic of Rose Island.' Here the woman narrator, named Georgia, tells the story of her late father, a rare stamp dealer, and her sister Lisa, who has disappeared somewhere in Europe.

Before leaving, Lisa was having an affair with handsome, rich Will, and is now pregnant. Will helps Georgia try to find Lisa, but slowly Georgia realizes that Will may not be as benign as he appears. Part mystery, part love story, it gains momentum without ever quite reaching its destination – which, in this case, more than satisfies."

A Slim Selection

"There are times when the mind hesitates to enter a substantial book, aware that it will not be able to do justice. [...] I look for the slimmest volumes, nothing more than a hundred or so pages, nothing that cannot be finished in one sitting. Surprisingly, there are many and the pile soon builds up. [...] So sometimes, four slim books can add up to more than four slim books. Or perhaps there are times when things simply resonate more."

Saturday, November 1, 2008

Villa des Roses

On my bookshelves, I have the entirety of Willem Elsschot's novellas translated into English. This impressive collection amasses three volumes: Cheese, Three Novels (a novella anthology containing Soft Soap, The Leg, and Will-'O-The-Wisp), and Villa des Roses. Had I more Flemish or Dutch litterateurs visiting my study, they would surely be impressed.

On my bookshelves, I have the entirety of Willem Elsschot's novellas translated into English. This impressive collection amasses three volumes: Cheese, Three Novels (a novella anthology containing Soft Soap, The Leg, and Will-'O-The-Wisp), and Villa des Roses. Had I more Flemish or Dutch litterateurs visiting my study, they would surely be impressed.Villa des Roses is a character-driven novella with an episodic plot. To be accurate, it is populated by at least thirteen characters -- I may have miscounted, for it could be more -- and most of the episodes take place within the Villa des Roses, a pension in Paris. One of the major characters, Louise, is introduced in the shortest chapter of the novella: fifty-six words and then in the very next chapter she is hit on by all the men at the Villa des Roses. Eventually, she will fall in love with Richard Grünewald. This affair is effectively and sympathetically realized.

Madame Brulot, the Madame of Villa des Roses, appears in almost of every chapter. Like the pension itself, she acts as a gravitational force for the action in the novella, for all the happens is noted and noticed by her. She is married and owns a pet monkey, who will be murdered in an alternatively horrific and darkly comic episode. The murderer, Madame Gendron, the decrepit resident kleptomaniac who is brilliantly featured in a chapter entitled "The Oranges," will manage her revenge without getting caught. And the reaction of Madame Brulot, in just one or two phrases, shifts the horrific episode into a comic banality.

There are various ideas about novellas only consisting of one central character in a limited time frame and within a limited action. In its character density (there are more characters per square inch in this novella than in any other I can recall), Villa des Roses shows that theories are quaint distractions that no author nor reader should heed.

While reading Villa des Roses, I couldn't help but think of the British comedy, Fawlty Towers. This novella has a sitcom atmosphere similar to that classic Britcom, yet it lacks the histrionically loud John Cleese. Most of the humor in Villa des Roses is deadpan and subtle. Elsschot is essentially a realist with a wicked and whispering sense of humor.

What's a director to do with a novella that reads thicker than its spine? The smart money would tell you to focus on a few characters in order to focus the narrative arc, even though other characters may minimized or left on the cutting room floor. By training the camera on Louise and Robert's tragic romance, the film version of Villa des Roses achieves a certain focus that novella may have lacked, but it ultimately suffers in substance and depth. Certain episodes seem out of place when interspersed with the love story. Madame Gendron's orange stealing scene feels unmoored and isn't funny, and her later revenge killing of Chico doesn't really make sense.

What's a director to do with a novella that reads thicker than its spine? The smart money would tell you to focus on a few characters in order to focus the narrative arc, even though other characters may minimized or left on the cutting room floor. By training the camera on Louise and Robert's tragic romance, the film version of Villa des Roses achieves a certain focus that novella may have lacked, but it ultimately suffers in substance and depth. Certain episodes seem out of place when interspersed with the love story. Madame Gendron's orange stealing scene feels unmoored and isn't funny, and her later revenge killing of Chico doesn't really make sense.Director Frank Van Passel does an admirable with the melancholic atmosphere of the novella. In the film's centerpiece, we see the tragedy of abortion and how it effects Robert and Louisa as well as other residents of the Villa des Roses. Were the entire film handled as well as this harrowing episode, it would have been a superb film.

Unfortunately, most of the subtle elements of Ellschot's comedy of manners are lost in this adaptation. Some of the initial scenes of Robert and Louise falling in love are touching and show the tension and uncertainty during the first blush of new love. On the whole, the comic dimension is muted and ineffective. Not too say that Elsschot's novella is a laugh riot, but its humor, whether dark or sardonic or witty, is always under the surface of each scene. The film's ending is trite and to a certain degree predicable -- rather unlike the novella's.

The film is heavy in the appropriate moments and these are its strongest scenes. But it fails when dealing with the novella's elegant, sardonic touch and its rich assortment of characters and their interaction with each other in the Villa des Roses. Julie Delpy's portrayal of Louise is wonderful and her onscreen relationship and interaction with Shaun Dingwall as Richard Grünewald is nuanced and believable. Shirley Henderson's Ella, the cook, acts as our tour guide and is a good foil for Delpy. Though Aasgaard is a minor character in both the novella and the film, Erik Vercruyssen does an admirable of making him memorable and reminds a reader of the novella that its minor characters add depth and texture.

It is one thing to say that the book is better than the film, which in the case is certainly true. By extension, the film has given me a greater appreciation of the novella and Elsschot's deft style. When I first finished reading the novella, I wasn't sure if I wanted to return to it again. After seeing the film, I know that I must book a return visit to Villa des Roses.

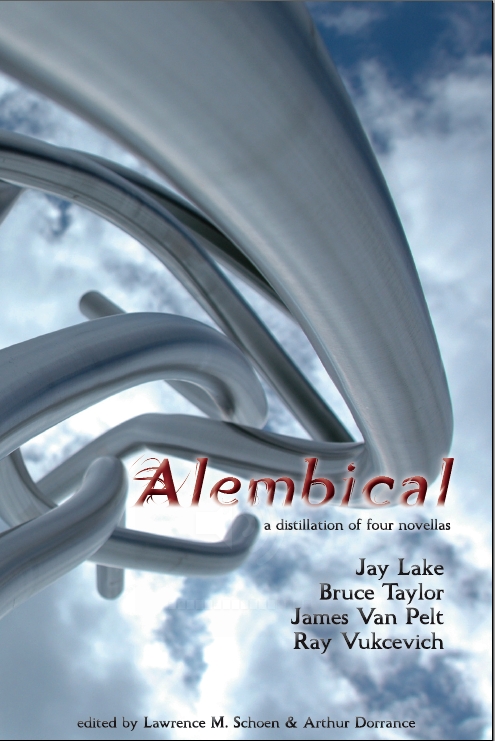

Alembical from Golem Press

A new anthology released today! From the website ...

A new anthology released today! From the website ..."Our second book, "unofficially" releasing at the World Fantasy Convention 2008 on November 1st, is Alembical, an anthology that extends Paper Golem's commitment to the genre by focusing on the novella, an all too often, under-appreciated length. Alembical gives voice to four of the field's most dynamic writers at the powerful novella length, leaping from sub-genre to sub-genre, and leaving the reader breathless in the process. This anthology will redefine your understanding of the novella."

Redefine my understanding of the novella? Sounds exciting! This is the first volume in an annual anthology featuring four authors: Jay Lake, Bruce Taylor, James Van Pelt, and Ray Vukcevich.

Friday, October 31, 2008

The Man In The Picture: A Ghost Story by Susan Hill

A truly chilling tale, The Man In The Picture haunted me as I read it. A story within a story and yet within another story -- quite apropos, frame story for a story about painting -- the overall tale is about a painting of a Venetian carnival and the characters within it, one of whom makes eye contact with viewers. As we get deeper into the scene and eventually deeper into the dark history of the painting and its subjects, we become drawn into a dark world of dread.

The telling of such a tale is supposed to relieve the teller of the secret burden of such supernatural occurrences. Yet when a tale is passed on, the hearer bears the burden and can become consumed with the horrific, inexplicable details. One knows that the tale is true, but also knows that it must not be true. For were it true, the truth would be too terrifying. Paintings are not supposed to change, especially after the oil has been dry for decades. The old saw tells us that life imitates art. The Man In The Picture explores that notion and scares us with its implications of mortifying mimesis.

Wednesday, October 29, 2008

Here's a toast to 'Tiffany's' on landmark novel's 50th birthday

Myra Overton has sailed here from England on the Queen Mary 2 to celebrate her 70th birthday. First stop: Tiffany & Co. on Fifth Avenue.

In her purse is an envelope addressed to "Mum." Inside is a homemade card sporting a photocopy of the iconic image of Audrey Hepburn with her long cigarette holder.

"You really can have breakfast at Tiffany's," reads the note from her son and daughter-in-law. It also says a gift card is waiting for her on the third floor.

"An American on the ship told me to forget about the movie and read the book," says Overton, who is from York, England. "He said it was the best thing Capote ever wrote. So I'm going out and finding it after I go in here."

That's impeccable timing on her part, because it's the 50th anniversary of Truman Capote's Breakfast at Tiffany's. A special edition (Vintage, $12.95, paperback) of the novella is being released in November, packaged with three other Capote classics, including A Christmas Memory.

Link.

Monday, October 27, 2008

Bookslut October Roundup

A History of the World for Rebels and Somnambulists by Jesus del Campo

"Enter the Spanish philologist Jesus del Campo and his slim, crazy, funny, History of the World for Rebels and Somnambulists, which is exactly what it says it is. It’s a roughly -- very roughly -- chronological account of world history, marked by the bravado and befuddlement of presidents, biblical figures, scientists, poets, magicians and God alike."The Bruise by Magdalena Zurawski

"Had I not completed Magdalena Zurawski’s prize-winning novel, The Bruise, with my fingers gripping the cover and its pages pressed beneath my thumbs, I might have questioned whether my astonishing literary odyssey was instead some feverish dream."Hail The Three Marys, a review of three novellas by Marie Darrieussecq, Marie-Claire Blais, and Marie Ndiaye.

"A trio of Maries, writing in their French mother tongue, have emerged on the literary scene, and have proved that they can break out of the gender mould, whilst remaining defiantly feminine. These talented women have relaunched the French novel on the international stage, and are forcing the critics to retract their draconian judgments."

Friday, October 24, 2008

A Golden Jubilee For "Things Fall Apart"

"Chinua Achebe's 'Things Fall Apart', which celebrates its golden jubilee this year, is Africa’s best known work of literature. The slim novel has been translated into 50 languages and has sold 10m copies. Never once has it been out of print."

From the Economist.

Saturday, October 18, 2008

The Day of the Owl by Leonardo Sciascia

In the post-Godfather cinematic imagination, the Mafia have always existed. Dons and their families have big weddings and ghastly shootouts in the booths of Italian restaurants. But after reading Leonardo Sciascia's The Day of the Owl, one realizes the Sicilian crime syndicate was once considered a myth, a legend born out of the aftermath of Fascist Italy.

In the post-Godfather cinematic imagination, the Mafia have always existed. Dons and their families have big weddings and ghastly shootouts in the booths of Italian restaurants. But after reading Leonardo Sciascia's The Day of the Owl, one realizes the Sicilian crime syndicate was once considered a myth, a legend born out of the aftermath of Fascist Italy.The novella's story is simple enough: a man is murdered on a bus and the crime is eventually solved by Captain Bellodi, an Italian from Parma but considered a foreigner by Sicilian standards. One of the Carabineri informants leaves a letter after his death (another murder) which links all the crime in the city to Don Mariano Arena, the local family boss. Though the case eventually goes to a high court in Rome, nobody is punished.

Written in 1961, it is difficult for us on the other side of the Godfather to imagine how dangerous it would have been for a writer, even one of fiction, to write anything about the mafia. Yet the coda tells otherwise: "One thing is certain, however: I was unable to write it with that complete freedom to which every writer is entitled." He further mentions that the reader shouldn't confuse the characters in his story with any "real person or actual occurrence." We see this caveat at the end of films or one of the front pages of other works of fiction as part of the required legalese, but to have the author pen a special coda (and thereby stepping out from behind the invisible narrator's curtain) makes one wonder what kind of peril Sciascia had entered by writing The Day of the Owl.

Friday, October 17, 2008

Untrue Confessions

"Two unreliable narrators perform a discordant but appealing duet in A Partisan's Daughter, a new short novel by Louis de Bernières, author of Birds Without Wings. One of them, Roza, a native of the former Yugoslavia, has long been missing; the other, Chris, a mopey old Englishman, reciting his story 30 years after the fact, comes under the heading of 'not dead yet.' He's had one great adventure in his life, and he tells the reader about it in the mopiest of tones. Life has more than passed him by. You might say that life has lapped him many times in the boring marathon of existence. But yes, just once, for a limited time, he fell under the thrall of a modern Scheherazade who (to quote the Beatles) 'filled his head with notions, seemingly."'The storyteller was Roza, and as he listened to her, his excruciatingly dull life was redeemed by the enchantment of narrative -- and the thought of future sex."

Tuesday, October 14, 2008

Amazon to Sell E-Lit Shorts for 49 Cents a Piece

"If it works for iTunes… Online retailer Amazon.com is offering digital-only bits of literature - Amazon Shorts - for 49 cents each, including samples from new authors, alternate chapters and scenes to well-known stories, one-act plays, classic short stories and memoirs from writers, reports Information week. Buyers can read the works or print them from the Amazon site, download them as PDF files or request that they be emailed as plain text.

Steve Kessel, Amazon.com's VP of digital media, is quoted by Reuters as saying, "We hope that by making short-form literature widely and easily available, Amazon.com can help to fuel a revival of this kind of work."

Publishers have always had a hard time selling and marketing the single, short-form work - the novella, or the novelette, or the even shorter "novelini" - he said."

Novelini.

The Novella Is A Peculiar Beast

"The novella is a peculiar beast. To play devil's advocate, it lacks both the succinctness of the short story and the scope of the novel, and often seems to provide a kind of halfway house for ideas that are too involved for the former, but too thin for the latter.

It also seems that the finest novellas eventually tend to be adopted by the larger family of the novel.

Do we really think of The Great Gatsby, Animal Farm, Heart of Darkness or The Outsider as novellas?"

Monday, October 13, 2008

The Novella As Feuilleton

A review of a release of a novella that existed in serialized form, but not in book form.

"As did many writers of the past," Bob Perreault explained, "Adelard Lambert published his novella as a 'feuilleton,' a serial novel in a newspaper. 'The Innocent Victim' appeared in several issues of Ottawa's daily paper, 'Le Droit,' but unlike his more fortunate colleagues, Lambert did not live to see his 'feuilleton' published in book form."

Adelbart Lambert's novella, The Innocent Victim, is available here.

Sunday, October 12, 2008

BRAVO! Light in the Piazza is brilliant!

"Patrons were on their feet Friday evening at the Stevens Center, giving Piedmont Opera's remarkable production of Adam Guettel's musical The Light in the Piazza a well-deserved standing ovation. James Allbritten, the show's conductor, had just taken a bow.

Oddly, the final curtain didn't fall as it usually does after the conductor walks on stage. Allbritten asked audience members to settle down and take a seat.

Elizabeth Spencer, who wrote the 1960 short novel on which Light is based, was in attendance, and Allbritten wanted everyone to see her stand before applauding her for the wonderful seed she had planted."

There is also a 1962 film adaptation.

Saturday, October 11, 2008

The Norman MacLean Reader

"Smartly edited by O. Alan Weltzien of the University of Montana, the book brings together manuscripts and letters found among Maclean's papers after his death in 1990, as well as hard-to-find essays, lectures and interviews. Maclean did not draw a distinction between his life and his fiction, and the material in the "Reader," much of it available for the first time, burnishes his achievement."

Friday, October 10, 2008

Novella News

Thursday, October 9, 2008

The Novella Hunter

I scanned the shelves. Not reading the titles and only occasionally tilting my head to the right, I made steady progress. At times, my head tilted as my hand reached up for a book -- not a thick brick, but a slender sliver.

I scanned the shelves. Not reading the titles and only occasionally tilting my head to the right, I made steady progress. At times, my head tilted as my hand reached up for a book -- not a thick brick, but a slender sliver.Best done in used book stores to avoid sticker shock, novella hunting yields wonders. The fat spines reel past my vision. Classic titles on slender spines catch my eye: The Great Gatsby, The Heart of Darkness, The Old Man and the Sea, Animal Farm, Of Mice and Men, Master and Man, Bartleby the Scrivener. And personal favorites beg me to buy to give to friends: The Fly-Truffler, The Club of Angels, Silk, The Lover. For such a misunderstood form, the novella hunter has an abundance to bag.

The same hunt can be done in a big bookstore, but the price is dear. Though slimmer than the double quarter-pounder novel, the novella costs the same as a novel, much like in wine shopping where 250ml bottle of dessert wine may cost as much or even more than a regular 750ml bottle of red wine. Like a dessert wine, the novella compresses its sentences and its words are hand-picked. Everyone bends an elbow for water, toasting with beer is common, and a few enjoy wine, but even fewer sip dessert wines. As any winelover will tell you, a Bordeaux may blow you away but only a Sauterne, particularily a Chateau D'Yquem, can be called the queen of wines. It must be sipped, too much would be too exquisite for any palate.

With any talk of wine and books, prose runs purple. And it becomes excessively so with considerations of the the novella. No definition suffices. Scholars propose plot limits; publishers submit page limits; contests recommend word counts. One author calls his one hundred page book a novel; another calls her two hundred page book a novella; a third dead one calls his fifty page book a nouvelle.

Publishers avoid using novella on book jackets to keep the price high, or they use it to justify the high price. Literary critics avoid writing clearly about it (and anything else). Novelists avoid it so that their books won't be blurbed as slim gems. Should we trust the author when he calls his book a novella? Doesn't the intentional fallacy prevent a reader from trusting what the author intends? Should we trust the publisher who only wants to justify the price?

If the book is perceived as being high-brow, the book will be a novella with a novel price markup. If the book is low-brow or somehow doubts itself, the book's title must have A Novel underneath it, almost as a foundation and a justification. Whom do we trust? How do we know what the book is to be called? Is it a novel, a short novel, a novella, a long story, or just a short story?

Who can claim authority? There exists no Novella Panel of North America to settle the score. As far as I know, the French have yet to award a special prix for the only novellas. Though the word has Italian origins, do the Romans travel literary roads seeking it? As the Delphic oracle urged self-knowledge, each reader has no choice but to choose for one's self. For every definition, there is a counter-definition. A reader may be unable to define exactly what a novella is, and actually have no real need to do so, but he knows one when he sees one on the shelf.

So the novella sits on shelves like Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, which Schubert described as a slender Greek maiden between two Norse gods, the genre-bending Third and the colossal Fifth. The gods roar and spread their thick arms demanding your attention, but ignore them and quietly recollect yourself. Scan the horizon for slender elegance, not brutal bombast. When you spy one you'll know it ... tilt your head and reach up.

Wednesday, October 8, 2008

Ivory Gazing

A portmanteau phrase pulled from my own neologistic noggin, ivory gazing stitches together two opprobrious terms and amplifies their disdain. The ivory tower is replete with professors stroking pointy chins who pronounce, pontificate and, natch, profess; navel gazing is an activity that solely preoccupies the bore whose navel endures the tedium of its owner's odd expression of ennui.

A portmanteau phrase pulled from my own neologistic noggin, ivory gazing stitches together two opprobrious terms and amplifies their disdain. The ivory tower is replete with professors stroking pointy chins who pronounce, pontificate and, natch, profess; navel gazing is an activity that solely preoccupies the bore whose navel endures the tedium of its owner's odd expression of ennui.My blog, Big Book Big Evil, requires the occasional essay addressing the philological and philosophical perplexities of the nimble and noble novella. When such an arduous article is needed, it will bear the tag ivory gazing.

The reader has been duly advised.

Sunday, October 5, 2008

Lit Flicks Challenge

And as per the raison d'être of BBBE, all five will be novellas. Out of the five I've selected, two I've read and seen, two are brand new, and one is a mystery.

The two that I've read and seen are Pascal Quinard's novella All the World's Mornings (Tous les matins du monde) and Marguerite Duras' The Lover. It's been a while since I've read and seen these two: at least a year and a half for the former; over a decade for The Lover. In both cases I saw the film before I read the novella; this time around I'll read the novella and then see the film. These two have been important to me, and I wonder how they stack up now.

In the spirit of exploration, I've selected two that I haven't read or seen: Villa des Roses by Willem Elsschot and Breakfast at Tiffany's by Truman Capote. I've read and reviewed Elsschot's Cheese and own an as-yet-unread collection of his novellas. Though I've seen the biopic Capote, I've never read Breakfast at Tiffany's nor seen the classic film with Audrey Hepburn. Yeah, yeah, I know -- but ars longa, vita brevis! So cut me some slack.

My final selection is a mystery -- not a whodunit or private detective story, but a true mystery. I have no clue as to what it will be, but I wanted to leave one space open for spontaneous discovery, serendipity if you will. Chance favors a prepared a mind. My antennae will be up and I hope that more novella-into-film adaptations will blip on the BBBE radar.

Here's the quick list for easy viewing:

- The Lover

- All The World's Mornings

- Breakfast at Tiffany's

- Villa des Roses

- a mystery

Saturday, October 4, 2008

The Book of Proper Names by Amélie Nothomb

I always enjoy reading Nothomb's novellas. Each one has enough quirks interspersed throughout to keep the eyes moving and the mind traveling toward the magnetic pull of the final page. And there is usually a certain magic about them, not magic realism, but a charmed realism.

I always enjoy reading Nothomb's novellas. Each one has enough quirks interspersed throughout to keep the eyes moving and the mind traveling toward the magnetic pull of the final page. And there is usually a certain magic about them, not magic realism, but a charmed realism.The Book of Proper Names is imbued with this charmed realism. About a beautiful slender dancer with a tragic past and a bizzare name, it tells the story of Plectrude's childhood and teenage years right up to the first blush of adulthood: first best friend, first love, first child. Though the final scene is abrupt and contains a cute riff on the "author's dead" trope, the novella as a whole fits together well. Like a good novella should, it reads quickly and uses its minimal space for maximum impact.

Nothomb's novellas often include autobiographical underpinnings; although the main character is Plectrude, we sense that it's just another mask for Amélie. The narrator of her novellas usually has the perspective of a child of around ten. Even though Plectrude (or any other Nothombian character) ages, the narrator in a charmed realism story must see the world as a ten year old:

Ten is the most sunlit moment of growing up. No sign of adolescence is yet visible on the horizon: nothing but mature childhood, already rich in experience, unburdened by that feeling of loss that assaults you from the first hint of puberty onward. At ten, you aren't necessarily happy, but you are certainly alive, more alive than anyone else.

This ten year old perspective is leavened with a bit of the if-I-knew-then-what-I-know-now authorial tone. And even if the character isn't ten, or doesn't age, the same tone will still be found. In Fear and Trembling, the main character (in another nod to autobiography, this one is named Amélie) is a stranger in a strange land who must live in a language environment that is quite foreign to their native one. Anyone who can speak a second level to at least the level of a common ten year old will know what a charmed life it is.

Nothomb uses the novella to describe herself and her view of the world. And so we read her novellas as a species of roman à clef. The actual experience in each scene may be fictionalized, but somehow her real life experience is felt lurking behind the fiction. Like the Wizard of Oz, whose real name was behind the curtain, Amélie Nothomb uses characters' names to distract from the author behind the page. And when we get to the final page and turn to the author's photo inside the back flap, we don't really care what about her real name or even if the events were actually real. Through her storytelling and odd characters and settings, we're charmed. And that's a real as we need in a novella.

Wednesday, October 1, 2008

Reflections on the Novella Challenge

Just over two weeks ago I stumbled upon and joined the Novella Challenge. Originally scheduled from April to September, other participants had joined and finished long ago. By time I joined, I had just finished reading Saul Bellow's The Actual and had a handful of novellas sitting on shelf that needed to be read. At first, I wasn't sure if I would blog about them. I worried that it would put too much pressure on me and that I'd give up.

I didn't give up and finished the challenge with one day to spare -- not quite the very last minute, but close enough. I'd read six novellas, written a couple of thousand words in seven blogs -- eight including this one; I also wrote a blog about novella hunting, which I will post later; and another blog with a list of novellas owned and read, which I will not post later. And I rekindled my novella passion.

Throughout my reading life, I've read novellas even though I didn't know that they were novellas: Heart of Darkness, Animal Farm, The Call of the Wild, The Old Man and the Sea, Bartleby the Scrivener. I probably encountered the term sometime in college -- perhaps after seeing the film The Lover and then tracking down the story, which I subsequently learned was not just a novel, but a novella. But I didn't really start obsessing over them until grad school when I read Gustaf Sobin's astounding The Fly-Truffler, which was so magical and transformative that I realized I never wanted to read anything over two hundred pages for the rest of my reading life. This was reinforced by further research and discovery of novellas by Tolstoy and Melville, and newer authors like Amélie Nothomb and Luis Fernando Verissimo, and new-to-me authors like Willem Elsschot, whom I'd reviewed several years ago. I had stacks of novellas next to my bed.

Then, I stopped. I graduated grad school, taught college, got divorced, went though a bout of depression and general aimlessness; all of which was made worse by my inability during that period to read any fiction, short or long. The only fiction I encountered was through film. My reading consisted mainly of Internet articles, non-fiction, and religious works; I was also going through a profound conversion to Catholicism, and afterwards read Tolstoy's Father Sergius during a weekend at a music and liturgy conference, a weekend that helped me decide to become, again, a full-time musician -- though not a liturgical one

And then I read a fantastic memoir, The Mystery Guest, by Gregoire Boullier. It read more like a story than a real memoir, for the story had far too many tidy coincidences. Most importantly, it was short and it reminded me of a novella.

This memory lingered a bit and I went back and read more Tolstoy, Master and Man, and also read Steve Martin's second novella, The Pleasure Of My Company, which made my novella torch shine a bit more brightly. But the novella that put my obsession on full stalker mode was Alessandro Baricco's Silk. Though a bit experimental, I reveled in it. It made me realize that I had to start reading fiction again (I still had a few non-fiction books to get through), though it took me a few more months to eventually borrow The Actual from my library and stumble upon the Novella Challenge.

And I am grateful. Due to a rough patch in my past, I'd lost something that I'd loved. I'd even almost forgotten about it. Now, I remember. And once again there are stacks of novellas next to my bed.

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Borges and the Eternal Orangutans by Luis Fernando Verissmo

This labyrinthine novella scared me. I wasn't really sure I wanted to read it. After reading Luis Fernando Verissmo's superb The Club of Angels, I wanted more. But this? Such a strange title. And what's with the Fernando Botero cover? I started reading it anyway.

And then I put it aside for over a year. It was just too strange, wasn't it? It sat on my shelf and I'd catch a glimpse of it and think ... shouldn't I finish it? It sat a while longer till the Novella Challenge gave me no excuse not to read it. What wonders I had avoided. A Borges fanboy, Vogelstein, tells the story about a murder at an Edgar Allen Poe academic conference in Buenos Aires to Jorge Luis Borges, who attends the conference and eventually makes a special contribution to this novella.

Vogelstein tells us, or rather, he tells Borges, "A conference on Edgar Allen Poe interrupted by a murder committed in a locked room, it was like a story by Poe himself!" Almost the entire novella is narrated to Borges. This locked room murder mystery also interweaves Borgian elements of arcane erudition and supernatural connections that any fan of Poe, Borges and even Lovecraft will revel in.

Locked room mysteries are troublesome. Usually the narrator can not be trusted. Something is always hinted at or barely glimpsed or quickly mentioned that holds the key to the locked room. If written properly, that something will be difficult to discern among the amazing array of facts and evidence. Red herrings and gold bugs and theories will crowd around us and prevent us from getting a good look at the room. Potential suspects will appear, but eventually dismissed. We shout eureka at the moment we think we've found the murderer only to suddenly realize that there is no way the Japanese professor could have gotten out of the locked room.

And so we read on until one of the characters clues us in and deciphers the mystery. In Borges and the Eternal Orangutans, the narrator abandons that role and hands the cipher to another character thereby plunging us deeper into the labyrinth. It took me over a year to sit down and finally read this novella; it will take much more than another year to get over this marvelous novella. I can't wait to read it again.

Friday, September 26, 2008

Lila Says by Chimo

Explicitly graphic and exquisitely gorgeous, Lila Says is part Catcher in the Rye, part Lolita, and part je ne sais quoi. Ostensibly written by Chimo, a writer-in-the-raw nineteen year old Arab boy living in the Parisian projects, Lila Says follows the relationship he has with Lila, a sixteen year old Roman Catholic girl. The novella is supposedly straight out of the notebooks sent in by Chimo, and some controversy ensued about the identity of the author.

Lila and Chimo's relationship begins with an act of heavy petting on a moving bicycle, which is as odd as would be expected. Though no other intimacies happen between them, Lila treats Chimo as a confidante and tells him her darkest and wildest sexual fantasies. She may have the face of an angel, but she has "all those words popping out of her mouth like snakes." Chimo is mute during most of Lila's serpentine monologues. It's plain that Chimo is a virgin, or at least very inexperienced, but he wants to know more -- yet he worries that he'll lose her if he does more. It's a complicated situation, for Lila offers every kind of devious delicacy that any modern nineteen year old would have problems passing by. She details buffets of debauchery, and Chimo can't wait to get home to record in his notebooks.

There is no spoiler in saying that this tragedy doesn't end well. But it is worth noting that the ending of the novella differs from the film adaptation with the beguiling Vahina Giaconte as Lila. I first came across the film and was so captivated by it that afterwards I ordered the DVD and tracked down a copy of the novella. The film and the novella differ in other ways: the film offers more background on Chimo and gets a bit deeper into his relationship with his ghetto friends; and, of course, the endings are significantly different, both tragically -- but one more so than the other.

Due to the very graphic language of this novella, it could easily be viewed as erotica and often leaps into pornographic lasciviousness. Erotica has literary pretensions; porn only wants to titillate. Some of the scenes that Lila describes are Penthouse-letter hardcore, yet they are juxtaposed with Chimo's perplexed innocence. The writing is at times fine and fresh, though other times it drags and is a bit dry.

And so there is a bit of moral quandary, is this filth or is this fine art? Perhaps it is a bit of both. Perhaps it exists in that gray world of filthy fine art. The book flap situates Lila Says between Marguerite Duras' The Lover and Pauline Reage's Story of O. In certain hands, these books would be banned and burned; in other hands, they would be regaled and recommended.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Old Herbaceous by Reginald Arkell

When traveling somewhere, it always feels good knowing that you know someone at your destination who knows the lay of the land. You can put away the guide books and just enjoy the sights. I felt like a traveler when I first opened Old Herbaceous. Subtitled "A Novel of the Garden," and set in England at the dusk of the Victorian era, I entered another world, one that has a trusted guide in Reginal Arkell. And having no clue about gardens, I had been introduced to a different country and culture than my suburbanite one.

Old Herbaceous is one of those novellas that hardly feels short, though it doesn't read long. The story is rich and covers the eight decades of Herbert Pinnegar's life, passing through youth, two wars and eventually old age. We read about his triumphs and struggles and learn volumes about him in just twenty chapters and one hundred fifty pages. Though some novellas revel in experimentation, Old Herbaceous tells a story. Nothing fancy, no tricks, no smoke and mirrors.

In the middle of Old Herbaceous lies the heart of the Pinnegar. About early strawberries and blue morning glories and touched with the dew of insight and respectful love, Chapter Ten is where we fall for him. We see into his true nature and know what kind of character we are dealing with. Although in general he can be crotchety, his heart is as well-kept and as beautiful as his garden.

One aspect I particularly enjoy about good novellas is that, like poetry, they can make apothegmatic observations. Here is one such garden gnome, "If you peel the years from a man's life, as you would the leaves from a globe artichoke, you would find him having his happiest time between the ages of fifty and sixty-five." This notion is exanded upon in a well-wrought passage, but I'll leave you with the pleasure of finding out how -- and there are more tidbits on gardening and human nature sprinkled throughout the novella.

I am an outsider when it comes to being outside. Part it has to do with living in a hostile and hot and humid climate, one that attracts virus-ridden mosquitoes, and part of it has to do with allergies and rashes. I like the idea of being outside, but being outside is always a bad idea. Mind that I have been in gardens, but I haven't a clue as to what the various names of the flowers and whatnot are. I can identify a rose and a dandelion and maybe an orchid, but I haven't a clue about morning glories or annuals or any Latinate flower. Colorblind, though not morbidly so, most of the intricate and delicate colors of the garden are lost on me.

One can only imagine what Herbert Pinnegar, the seasoned and wise gardener protagonist, would have thought of someone like me. Not much, I'm sure. But I will tell you what I think: I'm rather fond of him. It's difficult not to admire someone who finds his vocation early in life, excels at it throughout life, and is still passionate about it at the end of life -- even if that someone is only a fictional character. The greatest fictional characters are ones who we know do not exist in fact, though we feel that they nonetheless exist. Like Huck Finn or Jeeves, Pinnegar recalls those characters we've met and heard about in stories and also in life. We know that a character like Pinnegar is but a fictional creation, yet we feel that he is also just down the street tending his garden.

Friday, September 19, 2008

The Cuttlefish by Maryline Desbiolles

When is a novella a novella? Arguments shuffle around definitions based on word count, page length, narrative content, time elapsed within the story. What appears to be a novella could be something else. Glancing at its spine, Maryline Desbiolle's The Cuttlefish appears to be a novella, but the book cover clearly states that it is "A Novel."

Although the book's title indicates that it may be about cuttlefish, it is actually about a recipe for cuttlefish, but cuttlefish only in name for the opening sentence declares, "The recipe began with a mistake." The mistake? The original recipe for stuffed cuttlefish, copied down by the narrator, did not use cuttlefish, but calamari. Even when she goes to the fishmonger to buy cuttlefish, she buys the only thing available, calamari. Yet, mysteriously, the calamari is referred to as cuttlefish throughout the entire book. When you read cuttlefish, read calamari.

So what? Cuttlefish or calamari? One word or the other, they are close enough, right? Most likely they are just a few genes apart. It matters for it lets us know whether or not we can trust the narrator when she later says, "I follow the recipe word for word and don't allow myself the slightest deviation." But she does. She deviates. If a cuttlefish is actually a calamari and a novella is actually a novel, can we be sure of anything when reading this book? If words don't mean something, they can mean anything; and if they can mean anything, they can mean nothing.

Divided into twelve chapters each with each chapter's title being a step in the recipe, The Cuttlefish is an improvisational meditation on food preparation. The dish is being prepared for a dinner party, and the dinner party theme surfaces sporadically throughout the book. The recipe steps described at the beginning of each chapter usually have little to no bearing on the chapter's content. There are riffs on the dinner party, personal life history, aspects of preparing the food. Were this book a work of jazz it would be free jazz, a jumble of sounds loosely related and collected under one title. Moments of disjointed brilliance erupt only to be quickly subsumed by a cacophony of competing ideas. Chapter 7, "In a saucepan, sauté 2 chopped onions in 2 tablespoons of oil," is perhaps the best of the book, but by time the seventh chapter has been reached, who cares? The only reason to read is to indulge the author, an author acting like a spoiled child who cannot be corrected without a resulting tantrum.

Experimentation is an exciting aspect of the novella. New techniques and theories can be tested without testing the reader's patience for too long. But when the reader's patience is tested, the experiment fails.

Desbiolles' Cuttlefish experiment attempts to unlock the world of memories and associations that are inextricably linked with the sense-world of food. In a certain sense, she succeeds in capturing the capricious mind as it discursively meanders while engaged in the mundane aspects of food preparation. Whether or not she succeeds for twelve chapters and 113 pages is a test that the reader must embark upon and decide.

My decision is simple: read the chapters in any order you wish, read the whole thing or just a chapter or just paragraph, read experimentally. If cuttlefish can be calamari, and novellas can be novels, reading can be not reading.

Thursday, September 18, 2008

Emily L. by Marguerite Duras

What a wonderfully opaque and inebriated novella! An alcoholic French couple summers in a French port town and observes another alcoholic British couple, the Captain and his wife. The French couple essentially eavesdrops on the Brits, but since they can't hear everything they make up a history for the Brits, a history that is besotted with poetry and passion and drink.

This novella, filled with shifting perspectives, has postmodernist leanings. Even as we start to think we know who Emily L. is, we eventually doubt it. Surely, it wasn't that Emily, was it? But the line from "A certain slant of light" shows up and an unmistakable description of it is limned. Yet the Brits are from Newport, not Amherst. And they are Brits, not Americans. This can't be that Emily, can it?

Since the novella's main character narrates from inside a resort hotel bar, should we assume that the tale is one exaggerated and distorted by drink? I believe the tale is an excuse to delve into the themes of love and truth and especially writing. Writing is often a favorite topic of postmodernist authors, though I would hesitate to call Duras postmodern though she has written a pomo novella in Emily L. Though written during the postmodern era, Duras could be more accurately described as following the earlier theories of nouveau roman, which included author Alain Robbe-Grillet as its main author and theorist.

Emily L. abounds in savory nuggets for writers ...

- "The only real poem is inevitably the one that's lost."

- "When you die, the story will become legendary, flagrant."

- "She said if [the poems] made him suffer it probably meant that he'd begun to understand them."

The last page of the novella reads likes a manifesto for writing and, though it loses some of its power and eloquence quoted out of context, the final words of its last, sprawling sentence are an apt summation: "... just leave everything as it is when it appears." A bit of the first draft, best draft? Et tu, Marguerite?

One of the things I really enjoy about Duras' style (and this may be a refection of her being involved with the nouveau roman as mentioned above) is her ability to paint a scene or describe an emotion without the use of verbs, or at least use as few as possible. A classic example of describing an interior state comes out of her masterful novella, The Lover. After the girl's first sexual experience Duras writes, "The sea, formless, simply beyond compare." Something about not using a verb, and in the context of that transformative act, creates an eternal moment, suspended and cut off from the past and future, hanging in the forever present much like in the moment of intense sexual release.

In Emily L., she lessens the importance of the verb in all but one sentence to paint an especially vivid scene in the middle of the book: "Dusk. The light of dusk everywhere. The streets, the ships in the harbor. A gold, a pink and gold light that's reflected back from the bright surfaces of the tanker port on the other side of the river." One instance of verb usage, this passage is full of descriptive nouns all connected to "reflected."

And this is Duras' charm, her style. Though story is important in a novella, the form does allow for experimentation and for deep excursions into style. Story is part of why we read novellas, but there is also the need for understanding the inner lives of the characters in the story or even how the surrounding milieu can be considered psychologically and not as just merely props for the scene. And things in our own world take on a certain importance to our own lives, especially when we drink and fantasize and gossip and eavesdrop on our fellow drunks. This can be heightened on vacation -- when everything has a special glow and hidden meaning.

The novella opens with a simple declarative sentence, "It began with the fear." That fear is everything, anything ... love and loss of love, commitment and infidelity, life and death. And all are considered throughout Emily L. What would a writerly novella be without some consideration of death? What better vacationing barfly understanding of death than what comes from the Captain, "Drink will blur things when the time comes. Drink and dementia."

Not a first choice novella within Duras' work -- that distinction must go to The Lover -- but Emily L. shows a writer comfortable with her voice and especially gifted with experimenting within the novella form.

Monday, September 15, 2008

The Actual by Saul Bellow

I have a general, rather nasty rule about novels by post-Nobel Prize winning authors: Avoid. I'm sure that there are exceptions out there, but none that I can think of off the top of my head. The same thing applies to poets winning major awards, or that kiss-of-death post of poet laureate. Official posts and poets generally don't work too well. The same could be said for novelists winning famous prizes or getting jobs as creative writing instructors or professors -- jobs that involve teaching writers how to write washes out the writing for authors.

The Actual offers interesting insights into Sigmund Adletsky, Amy Wustrin and the main character, Harry Trellman, but the plot gets blurred in what reads more like a character study than a novel. Harry Trellin has a life-long obsession with Amy and never gets too far in declaring his love for her; Adeltsky helps them reunite. The last scene of the book is compelling and odd. Some interesting insights into upper crust Jewish society, but in general this novella reads long for its one hundred and four pages. There were times while reading this that I wasn't exactly sure how a particular scene related to the whole.

Saul Bellow won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1976 for Humboldt's Gift, his eighth novel. His first, Dangling Man, was written almost thirty years prior to it. Bellow was a just over sixty when graced with the Nobel. Isn't this a common practice of the Nobel committee to award the prize when the author has grayed a bit? They probably didn't anticipate him living another four decades. The Nobel Prize in Literature must be the most highly celebrated pink slip in history. It's the gold watch and pension, but in an age beyond gold watches and pensions I'm not sure if it means anything anymore.

I've heard that Bellow returned to the novella as he aged. If this is true, then this late turn may be similar to Tolstoy (never won the Nobel, by the way). Not sure why Bellow has turned to the novella, and I haven't read the one that is considered his best, Seize the Day ... so anything I say about Bellow is based soley upon The Actual. And I confess to my uncharitable and one-dimensional view on an author who probably deserves my greater attention. Unfortunately, my initial exposure to The Actual hasn't left the greatest of first impressions and I will be reluctant to return to him.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

μεγά βιβλίον μεγά κακόν

Big book, big evil.

This blog's title comes from the Greek poet Callimachus, who rallied against the old, long-winded poetry and advocated a terser verse. Though novellas are not poetry, they do run short. I've been a fan of the novella for a while, but I haven't really read many recently.

Earlier this weekend, I ran across The Novella Challenge and thought I'd join in reading the six novellas -- even though I'm a late entry! It ends Sept 30, so I've got to buckle down and get reading.

Just read Saul Bellow's The Actual (1997) over the weekend. The remaining five will be, in no particular order ...

- Lila Says (1996) Chimo

- Emily L. (1987) Marguerite Dumas

- Old Herbaceous (1950) Reginald Arkell

- The Cuttlefish (1998) Maryline Desbiolles

- Borges and the Eternal Orangutans (2000) Luis Fernando Verissimo