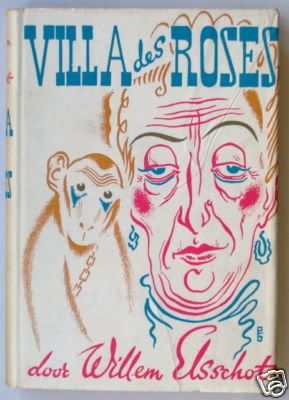

On my bookshelves, I have the entirety of Willem Elsschot's novellas translated into English. This impressive collection amasses three volumes: Cheese, Three Novels (a novella anthology containing Soft Soap, The Leg, and Will-'O-The-Wisp), and Villa des Roses. Had I more Flemish or Dutch litterateurs visiting my study, they would surely be impressed.

On my bookshelves, I have the entirety of Willem Elsschot's novellas translated into English. This impressive collection amasses three volumes: Cheese, Three Novels (a novella anthology containing Soft Soap, The Leg, and Will-'O-The-Wisp), and Villa des Roses. Had I more Flemish or Dutch litterateurs visiting my study, they would surely be impressed.Villa des Roses is a character-driven novella with an episodic plot. To be accurate, it is populated by at least thirteen characters -- I may have miscounted, for it could be more -- and most of the episodes take place within the Villa des Roses, a pension in Paris. One of the major characters, Louise, is introduced in the shortest chapter of the novella: fifty-six words and then in the very next chapter she is hit on by all the men at the Villa des Roses. Eventually, she will fall in love with Richard Grünewald. This affair is effectively and sympathetically realized.

Madame Brulot, the Madame of Villa des Roses, appears in almost of every chapter. Like the pension itself, she acts as a gravitational force for the action in the novella, for all the happens is noted and noticed by her. She is married and owns a pet monkey, who will be murdered in an alternatively horrific and darkly comic episode. The murderer, Madame Gendron, the decrepit resident kleptomaniac who is brilliantly featured in a chapter entitled "The Oranges," will manage her revenge without getting caught. And the reaction of Madame Brulot, in just one or two phrases, shifts the horrific episode into a comic banality.

There are various ideas about novellas only consisting of one central character in a limited time frame and within a limited action. In its character density (there are more characters per square inch in this novella than in any other I can recall), Villa des Roses shows that theories are quaint distractions that no author nor reader should heed.

While reading Villa des Roses, I couldn't help but think of the British comedy, Fawlty Towers. This novella has a sitcom atmosphere similar to that classic Britcom, yet it lacks the histrionically loud John Cleese. Most of the humor in Villa des Roses is deadpan and subtle. Elsschot is essentially a realist with a wicked and whispering sense of humor.

What's a director to do with a novella that reads thicker than its spine? The smart money would tell you to focus on a few characters in order to focus the narrative arc, even though other characters may minimized or left on the cutting room floor. By training the camera on Louise and Robert's tragic romance, the film version of Villa des Roses achieves a certain focus that novella may have lacked, but it ultimately suffers in substance and depth. Certain episodes seem out of place when interspersed with the love story. Madame Gendron's orange stealing scene feels unmoored and isn't funny, and her later revenge killing of Chico doesn't really make sense.

What's a director to do with a novella that reads thicker than its spine? The smart money would tell you to focus on a few characters in order to focus the narrative arc, even though other characters may minimized or left on the cutting room floor. By training the camera on Louise and Robert's tragic romance, the film version of Villa des Roses achieves a certain focus that novella may have lacked, but it ultimately suffers in substance and depth. Certain episodes seem out of place when interspersed with the love story. Madame Gendron's orange stealing scene feels unmoored and isn't funny, and her later revenge killing of Chico doesn't really make sense.Director Frank Van Passel does an admirable with the melancholic atmosphere of the novella. In the film's centerpiece, we see the tragedy of abortion and how it effects Robert and Louisa as well as other residents of the Villa des Roses. Were the entire film handled as well as this harrowing episode, it would have been a superb film.

Unfortunately, most of the subtle elements of Ellschot's comedy of manners are lost in this adaptation. Some of the initial scenes of Robert and Louise falling in love are touching and show the tension and uncertainty during the first blush of new love. On the whole, the comic dimension is muted and ineffective. Not too say that Elsschot's novella is a laugh riot, but its humor, whether dark or sardonic or witty, is always under the surface of each scene. The film's ending is trite and to a certain degree predicable -- rather unlike the novella's.

The film is heavy in the appropriate moments and these are its strongest scenes. But it fails when dealing with the novella's elegant, sardonic touch and its rich assortment of characters and their interaction with each other in the Villa des Roses. Julie Delpy's portrayal of Louise is wonderful and her onscreen relationship and interaction with Shaun Dingwall as Richard Grünewald is nuanced and believable. Shirley Henderson's Ella, the cook, acts as our tour guide and is a good foil for Delpy. Though Aasgaard is a minor character in both the novella and the film, Erik Vercruyssen does an admirable of making him memorable and reminds a reader of the novella that its minor characters add depth and texture.

It is one thing to say that the book is better than the film, which in the case is certainly true. By extension, the film has given me a greater appreciation of the novella and Elsschot's deft style. When I first finished reading the novella, I wasn't sure if I wanted to return to it again. After seeing the film, I know that I must book a return visit to Villa des Roses.