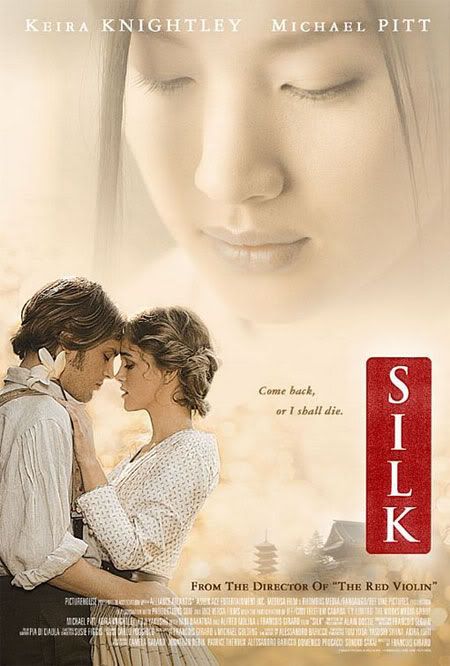

In what ways can unrequited love occur? The classic tale requires that one falls for another who cannot return the love, and its variations are manifold. Alessandro Baricco's Silk imagines unrequited love happening between the last two people on earth that we'd expect.

In what ways can unrequited love occur? The classic tale requires that one falls for another who cannot return the love, and its variations are manifold. Alessandro Baricco's Silk imagines unrequited love happening between the last two people on earth that we'd expect.Hervé Joncour travels from his village in France to Japan once a year to purchase the silkworm eggs necessary for his village's industry. While in Japan, he falls for his contact's concubine, the only woman in Japan without oriental eyes. He never speaks to her, but she does give him a short letter. He returns to Japan several times, partly on business but mainly to see this woman again. Eventually, war intervenes and his trips must end but he receives a final letter written in Japanese that will unravel his life.

Each chapter is meticulously brief. Baricco's prose is as light and effortless as finely wrought silk; it rests delicately upon the tale. Although Silk could be read in a sitting, reading it at a rapid rate is barbaric. I wanted to linger over each page and luxuriate in each scene and bask in the sparse, yet intimately revealing, dialogue. Like rubbing the finest silk between your fingers, feeling its airy nothingness and wispy delicateness, Baricco's novella slows you down into a state of quiet wonder as you marvel over how such a thing could be made.

It is a cliche that the highest praise offered for prose is that it reads like poetry. Perhaps this is true of this novella, though I'd prefer to go overboard and call it prose poetry. Words and meanings are compressed into the smallest of possible spaces, but still allowed to range across the page and across a tale in their sometimes quickstep and sometimes ambling rhythms. Prose poetry is difficult enough to define, and the same difficulty of definition haunts the novella. Throw the two together and a patchwork portmanteau genre is created, the prose poem novella.

Of the many ways of representing love on the screen, three are currently in style. The raucous, humorous path of ribaldry is common enough, as is the vulgar and impatient voyeurism of pornography. Though the erotic may contain elements of both ribaldry and pornography, it tends to favor the slow glance rather than the mocking stare of ribaldry; it favors the lingering touch, not the interminable pounding of porn. The erotic is subtle and nuanced. A body is nude, not naked; to not know the difference is to not know when the erotic is present.

François Girard's film adaptation of Silk is an erotic film that revels in understatement. Visually alluring, it is a patient film filled with exquisite moments: the tea ceremony where Hervé first notices the concubine; Herve sitting by the window and watching Hélenè wander the garden with a lighted globe; the bathhouse scene is a delicate depiction of seduction.

Michael Pitt (brother of another famous Pitt) does a decent job as Hervé Joncour. Though it is a subtle performance, it isn't very detailed. Kiera Knightley is even-handed, and her potrayal of Hélenè is weighted toward the beginning and the end without much in the middle. A better Baldabilou could not have been found than Alfred Molina. The moment he appeared I nearly jumped from my seat to shout, "It's him!"

Though just over one hundred minutes long, Silk caresses each minute. Some reviews I've read complain that the film is slow, a criticism that makes me wonder if the book had been read or if the reviewer was just another contemporary victim of caffeinated carnality, unable to slow down and meander through this garden of a film. For such a speed freak, I wouldn't recommend Silk. Perhaps coarser viewers would prefer Burlap?